Eberhard agreed with Nietzsche that “the church’s foundation is built upon the very opposite of the Gospels”; that the church is “a terrible hodgepodge of Greek philosophy and Judaism, of asceticism, of hierarchical order, etc.” Further, he shared Nietzsche’s view that originally Christianity “tolerated no connection with politics and state policies; it cannot in any way be a religion of the masses.”

At times Eberhard’s trenchant analysis of the established churches goes even further than Nietzsche’s criticisms. In the everyday life of the churches of his time Eberhard was hard-pressed to discover any argument to weaken Nietzsche’s objective criticisms of Christianity. To do this he had to go back to “early Christianity, as described in the Acts of the Apostles and in the New Testament epistles.”

In other words, Eberhard could not and would not in any way defend the “Christianity” that Nietzsche had in mind when he made his sometimes accurate observations and sometimes grossly abusive attacks. Eberhard painted a picture of New Testament Christianity that exposed Nietzsche’s accusations – “decadent,” “life negating,” “feeble,” “religion of pity,” etc. – as crass and arbitrary misinterpretations. Eberhard’s critique was that Nietzsche had made it too easy for himself; he recognized false Christians but had too quickly given up the search for true ones.

Eberhard’s dissertation co-opted Nietzsche’s language and thoughts to express spiritual truths, and refute Nietzsche’s using Nietzsche’s own idiom and arguments.

For Eberhard, Jesus is the “Übermensch,” the “overman” Nietzsche sought. Jesus is “the redeeming man of great and overcoming love, the creative spirit, the noonday bell that calls for a great decision, the one who sets people’s will free again, who brings the earth back to its true purpose and restores hope to humanity.”

For Eberhard, belief in Jesus meant affirmation of life, not at all the yearning for death, as Nietzsche had asserted; affirmation of the body, not self-chastisement or contempt of sexuality; and affirmation of nature and its gifts, not false asceticism.

For Eberhard, the Gemeinde – the church-community of Jesus’ disciples – is the “extraordinary, new aristocracy,” the “higher type of humanity” that Nietzsche had invoked. Eberhard identified the true Christians as Nietzsche’s “future masters of the earth” because, according to Revelation 20:4–6 and 22:5, at the end of time they will live and reign with Jesus.

For an entire decade Eberhard used slogans and illustrations from Nietzsche’s works to draw to his lectures both the critics of the church and the “born-again” Christians. These themes included: “The Bankruptcy of the Religious Systems,” “The New Aristocracy,” “Jesus and the Fight against Moralism,” “The Overman,” “The Will to Power and Submission to God,” “The New Humanity,” “The Modern Antichrist and His Defeat,” “Nietzsche in the Present-Day Struggle,” and “The Descendants of Humanity and the Coming Order.” However much these writings and lectures may have differed in detail, the basic theme remained the same: Jesus fulfills what Nietzsche could at best only long for. If a person desires “to set the stamp of eternity on his own life,” to use Nietzsche’s expression, there is no need to wait for an “eternal recurrence.” The best course is to hold to Jesus.

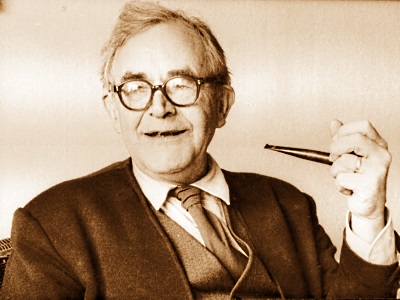

Adapted from Markus Baum, Against the Wind: Eberhard Arnold and the Bruderhof, electronic edition (Walden, NY: Plough, 2015), 45–46.