The Pentecostal spring of the early Christian Church stands in the strongest contrast to the icily rigid Christianity of our day. Everyone feels that there a fresher wind blows and purer water springs, that there a stronger power and a more glowing warmth hold sway than is the case today among those who call themselves Christians.

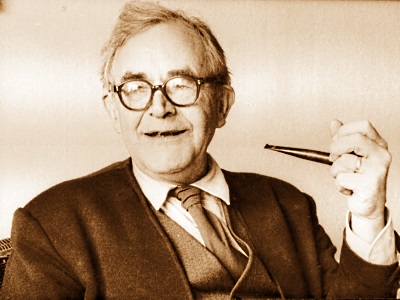

- Eberhard Arnold

Summary

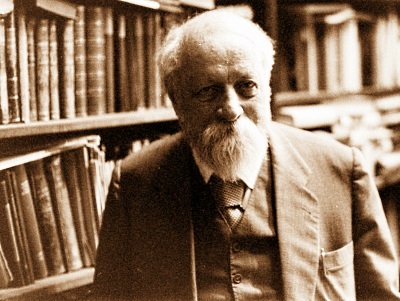

Eberhard Arnold’s deep interest in church history and world religions was likely kindled by his father, Carl Franklin Arnold, who was a professor of church history at Breslau University. From his conversion at sixteen to the end of his life, Eberhard drew on the witness of movements from the past to inform his own faith.

Early in his studies Eberhard encountered the Anabaptist movement of the sixteenth century, which he saw as offering a way of true discipleship. “They strived to live as close as possible to the way the early church had lived,”[1] he concluded. Eberhard was particularly interested in the writings of Anabaptist leaders such as Jakob Hutter, Sebastian Frank, Peter Riedemann, Hans Denck, Peter Walpot, Hans Hut, and many others.

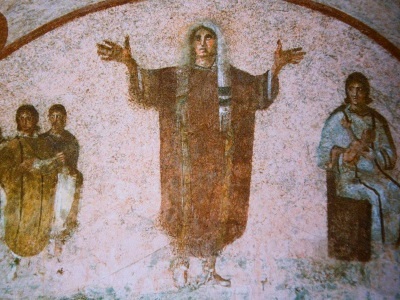

He was equally enthusiastic in his study of early Christian sources, culminating in his book published in 1926, The Early Christians, with selections from Tertullian, Origen, Iraneus, Hermas, Ignatius, Justin, and others. He saw this nascent, apostolic Christianity as truer to Christ’s calling than the forms it would later take, while holding out a “paradigm” for renewal: what was given to the early church through the Spirit can be and is given again and again to those who seek it.

In his treatment of forerunners to the Anabaptists, Eberhard made reference to the “apostolic brothers,” a loose connection of figures and movements that precede and flow into the radical Anabaptist movement of the sixteenth century. They include Arnold of Brescia, Peter Waldo and the Waldensians, the Poor in Christ, Francis of Assisi, Thomas à Kempis, Meister Eckhardt, Jacob Böhme, the Beguines and Beghards, Jan Hus and the Bohemian Brethren, the Unitas Fratrum and Moravian church, and the Brethren of the Common Life.

Eberhard argued that these various strands exemplified “a mysterious organic unity.”[2] Prior to the nineteenth century, many of them had been discounted by historians as “heretics” or wayward sects. Following the lead of several scholars of his day, however, Eberhard said that these witnesses testify most radically and faithfully to the gospel, to “the words of Jesus, especially the Sermon on the Mount, his life and the redemption he brought. Their freedom was based on the gospel; they desired no other freedom. Therefore their watchword was the imitation of Christ, the discipleship of Christ.”[3]

In Eberhard’s frequent reference to these witnesses, Francis of Assisi – with his apostolic poverty and his love of the poor and of nature – stands out especially. Eberhard appreciated and respected the Catholic tradition of monastics, and sometimes referred to the Bruderhof as “Protestant monasticism.”

On the other hand, Martin Luther was central to Eberhard’s theological training as well as his faith journey. Although Eberhard departed from Luther’s Reformation, siding with the Anabaptists, Luther’s understanding of sin and the cross were formative in Eberhard’s understanding of God’s grace. He was also influenced by Caspar Schwenckfeld, another leader of the Protestant Reformation. While rejecting the authority of the Catholic pope, Schwenckfeld warned against turning the Bible into a paper pope. He emphasized the workings of the Holy Spirit in granting faith and understanding.

The Moravian tradition of pietism gave rise to many thinkers who had a deep impact on Eberhard: Philip Spener, Hermann Francke, Johann Arndt, and especially the father and son Johann Christoph and Christoph Friedrich Blumhardt. Another important influence was Nikolaus von Zinzendorf, a bishop in the Moravian church whose Herrnhut community helped inspire the first Bruderhof settlement.

Eberhard also greatly admired George Fox and the first Quakers, comparing them to the Anabaptists of the sixteenth century: “Both movements want inspiration, guidance by the Holy Spirit, instead of the outward letter. Both movements believe that the church becomes unanimous by the inner infusion of the Holy Spirit, so that as a result of the inner voice of the Spirit in hearts the church unites in a common faith, a common resolve, and a common message.”[4]

Eberhard emphasized the importance of the Old Testament prophets and their prophetic spirit because they represent God’s will for justice and the eschatological longing for the peaceable kingdom. “The mystery of the church transcends time,”[5] he wrote. In every age there exist prophets, although what was given to the Old Testament prophets was a unique vision of the coming Messiah.

Eberhard believed that God revealed himself in many ways outside the Bible. While such revelation was partial, unfulfilled, and inadequate, he believed witnesses of truth exist in every age. He often referenced Zoroaster, Buddha, Socrates, and Lao Tzu. As sacred as the Scriptures are, Eberhard believed they should be read from within a larger context of God’s general revelation in nature and prior revelation to humanity. Only then can we truly grasp the Bible’s significance. Yet the ultimate goal was clear: “The further we would go in this search from person to person, from heart to heart, the clearer it will become to us that Jesus is unique.”[6]

1. Eberhard Arnold, “The Hutterian Brothers” (EA 31/29), 1931.

2. Eberhard Arnold, “The Mystery of the Early Church” (EA 20/10), 1920.

3. Eberhard Arnold, “The History of the Anabaptist Movement in Reformation Times” (EA 504), 1935.

4. Eberhard Arnold, “Concerning Original and Modern Quakerism” (EA 358), 1935.

5. Eberhard Arnold, “Prophets” (EA 25/09), 1925.

6. Eberhard Arnold, “Humanity and Community” (EA 21/26), 1921.

Selected Reading

The Economy of the Early Church

Eberhard Arnold

In an age when Christianity is comfortably entwined with consumer capitalism, the early Christians’ passion for social and economic justice can come as a shock. So why did the first Christians abandon private property? Eberhard Arnold addresses this question in an excerpt from the introduction to The Early Christians (1926).

Continue ReadingThe Spirit of the Early Church

Eberhard Arnold

The early church was not perfect, nor can it be blindly imitated, admits Eberhard Arnold in this groundbreaking 1926 essay. And yet, never since in church history has the Spirit been so forcefully at work. Why has the example of the first Christians never ceased to fuel renewal and reform?

Continue ReadingThe Early Anabaptists – Part II: Anabaptism in the Reformation

Eberhard Arnold

Persecuted by Catholics and Lutherans alike, these sixteenth-century Christians faced arrest and execution by the thousands for their beliefs. Learn more about the roots of a renewal movement that threatened the power of both church and state.

Continue ReadingThe Jesus of the Four Gospels

Eberhard Arnold

We live in an age where it seems Jesus has become almost unknown or his words distorted and disfigured, his work weakened. All the more, we must rediscover this Jesus and hold him up before all the world. We must place the Jesus of the four Gospels in the center of our faith and our life.

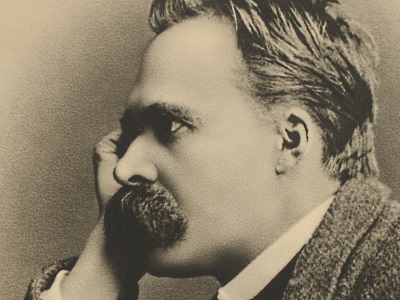

Continue ReadingEberhard Arnold and Nietzsche

Markus Baum

Friedrich Nietzsche’s philosophy, language, and thinking were of great interest to Eberhard Arnold. He completed his doctoral dissertation on Early Christian and Anti-Christian Elements in the Development of Friedrich Nietzsche, and from then on traces of the great impression made on him by this eccentric and extraordinary thinker surfaced in his thought, speech, and action.

Eberhard Arnold and Judaism

Eberhard Arnold sent his children to visit the local synagogue as part of their religious education and developed in them a deep respect for Judaism and its foundation, the Hebrew Bible / Old Testament. The following offers a brief survey of the Bruderhof's interaction with the Jewish community in their area.

Eberhard Arnold and Dietrich Bonhoeffer

While studying in England in 1934, Eberhard Arnold’s son Hardy came in contact with the community of German émigrés living in London, including the German pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer. He found that Bonhoeffer had a keen interest in his experience with communal life at the Bruderhof and in Eberhard Arnold’s writings.

Continue ReadingQuick Quotes

We experience that unity is at the same time agreement with the apostolic testimony of the New Testament, and agreement with the testimony of the future of the kingdom of God. Thus we experience unity not simply in the small circle of our community life, but as a unity that embraces all millennia; the spirit of inspired men and prophets; perfect unity with all original movements that were a spiritual uprising, with all movements, which sprang from the source, borne by the Holy Spirit and led by the inner light. We can testify that we have experienced that we become completely unanimous, when in the quiet hour the Spirit gives witness, and the light of Christ bursts into flame in our hearts, when in this silent concentrated attention the voice of Jesus speaks within us.

- Eberhard Arnold

One sign of apostolic mission and outreach by all movements of the spirit in earlier Christianity and later the Hutterites is this: while it is the custom of the institutional churches and religious gatherings of all kinds, to prepare their meetings with propaganda and the ringing of church bells and illuminated advertisements, the apostolic messengers follow, from place to place, the active Spirit, who tells them where the expectant and prepared hearts are to be found, where the people are who are moved and touched by God’s Spirit, so that the decisive message may be brought to them. Such men are to be found everywhere. We must be led to them through the Holy Spirit who guides us; they must be led to us through the Holy Spirit who leads them.

- Eberhard Arnold